Contents

BACK TO BACK AND FACE TO FACE

This routine is helpful to support wait time, movement, and collaboration with a new partner. The routine is best suited for questions requiring some thought. Direct students to find someone new to work with and then to stand “back to back” until you tell them to turn. Give them the prompt or question to think about. After a few seconds of thinking time, direct them to turn “Face to Face” and share their responses. Make sure students know who will speak first, and how long they will each have to speak. When time is up, direct them to return “Back to Back” and await the next prompt. Repeat the procedure with however many prompts there are; usually two or three times is a good number of times to go through the sequence.BEACH BALL

Make discussions fun, using one of the many versions of this routine. Read the ideas below and then adapt for your students. Be creative! Version 1- Seat students in a circle or in any configuration where everyone can see each other.

- Crumble a piece of paper into a ball (or use a soft ball of tossable size).

- Start the discussion with a question and toss the ball randomly to a student.

- The student answers the question and repeats with a classmate.

- According to the prompt you provide, throwing students will ask a new question or repeat the original question. Catching students will either answer the new question or provide another answer to the original question.

- Write questions on a white ball (any size, but soft enough to safely toss and catch, e.g., beach ball, volley ball, ping pong ball; NOT a golf ball or baseball).

- Seat students on their desks, in a circle, or outside, any place where everyone can see each other.

- Toss the ball to a student to start the game. He or she must answer the question that a specified finger touches, e.g., right pinky, left thumb, etc.

- Have students continue the game of catch, answering questions.

- Follow the steps for Version 1, but retrieve the ball after each student answers and toss it to a new student. This variation allows you to control who answers—everyone, particular students, etc—and also keeps the activity brief.

BRAIN BREAKS

Brain breaks are fun activities that provide space for mental and cognitive refresh. Research shows tremendous value for learning from such breaks, which enable students to return to learning ready for more effort. Use these criteria to develop brain breaks. Brain breaks:- should last about 5 minutes.

- should be fun, possibly with simple prizes for winning if a game.

- can be related to the lesson instruction/content OR be totally unrelated.

- Lists: Set a time limit. Then have students list as many examples of something they can, whether academic or totally silly (places to go; foods of a certain color; knock-knock jokes).

- Picture games: Use websites such as Spot the Difference to have students play visual games.

- Memory games: Collect items where students can see them. Display the items briefly and challenge students to memorize what they see. Cover the items and see what students can remember. Make the items fun and grade-level appropriate.

- Speak on the spot: Collect slips of paper with fun or serious topics written on them. Mix in a bowl or bag. Have students—independently or in groups—pick one or more topics. Allow just 1 minute for thinking, then have students say whatever they can about the topic. Allow students to pass or choose a new topic, but remind them that the activity is not a test and should be fun.

- Word games: Play a game such as hangman or find the word or Bingo or scrambled letters. For find the word, start with a relevant phrase, such as Good morning class or any other phrase you use often. Challenge students to find words within it, to reorganize the letters to make new words, etc. Be creative in using these games. Hangman can start with any word. Students can choose the word and start the game.

- Get Moving: Games that get kids out of their seats can be very effective brain breaks. Here are a few ideas.

- Challenge and Move: Have all students stand next to their desks or stand in a circle. Show a stimulus, such as a flashcard, or ask a question, to one pair of adjacent students. First student in the pair to supply the correct answer moves one desk or position around the room to pair with another student. Continue until all students play, with the goal of one student making it all the way around. (You probably won’t complete the game in 5 minutes but you could continue it over several brain breaks.)

- Pass the (fill in the motion): Have students face a neighbor. Looking at each other, they must clap their hands at exactly the same time. One student then turns forward and one repeats the pass with another neighbor. Like a wave, the action moves around the room. You can vary with words, such as move, great, go, or any word that inspires and encourages your students.

- Simon says and variations: Have students mingle. On your signal, they must collect in groups of a specified size OR they must freeze OR they must sit down OR whatever direction you have set.

- Timer Games: How many words on a list can you say correctly in X time? How many jumping jacks can you do in X time? Timer games let kids be competitive in a supporting environment and offer those struggling with academic tasks a chance to feel successful.

- Scavenger Hunts: Another game that probably has to be played across several brain breaks. Students will enjoy the change to continue.

- Add to it: Write a few entries in a list, or first sentence of a story, or first few lines of a name poem. Post it on a chart. Students take turns adding to it. Make it a memory game by writing the whole list, paragraph, poem, etc. Have students take turns reading one sentence on the chart and returning to a group to repeat. The group records in writing. Continue until the students have memorized and repeated the entire chart. Compare to the original. The game of telephone is a simpler version of this activity for younger students.

- Write Write Write: Have students free write for X time about a topic you supply OR a topic of their choosing. Some starters are favorite place to go after school; favorite food to eat; new ending to a favorite story; what a stimulus (picture, music, sentence, story, today’s weather, etc.) makes them think, feel, or visualize.

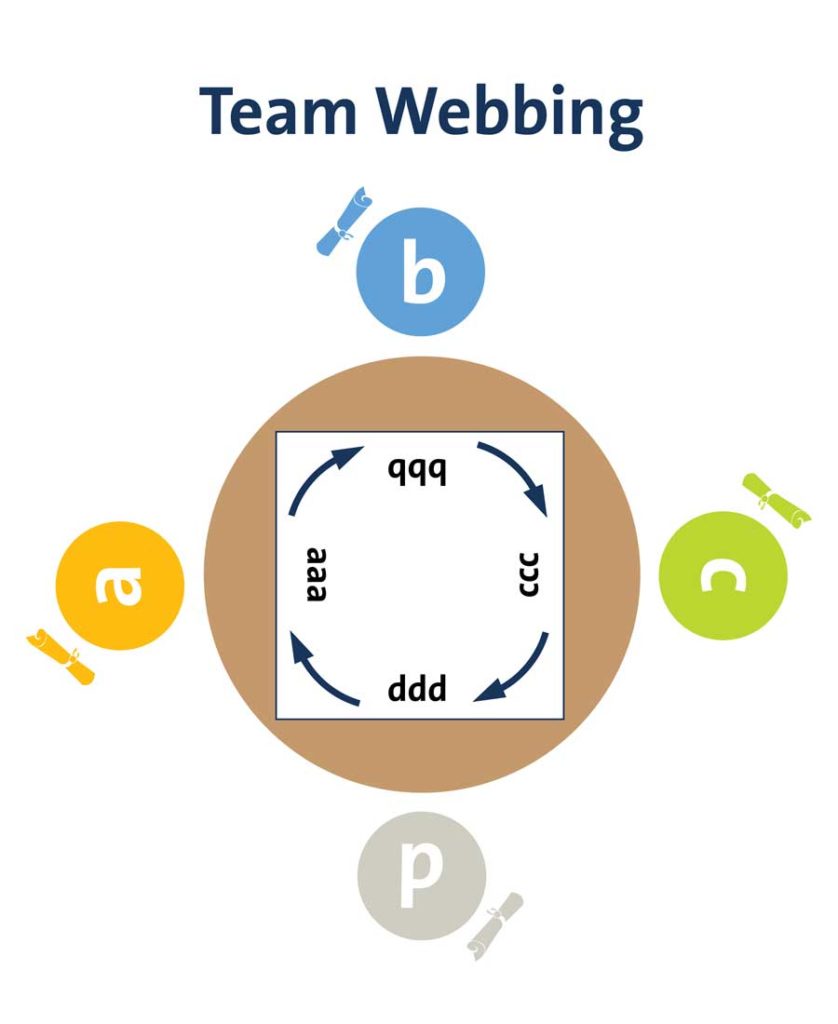

- Drawing: Have students collaboratively complete a drawing. Use a format such as Team Webbing, in which students have a giant piece of paper and turn it to add to the drawing. Make this activity serious or silly by providing either narrow direction for what to draw or giving students freedom to imagine.

COLD CALL

Call on students, one at a time or in pairs/groups, to answer. Use this routine when you expect students to know the answer or introduce it by saying that students may not know the answer but should do their best. Incorporate wait time to allow students sufficient thinking time.CONTINUUM

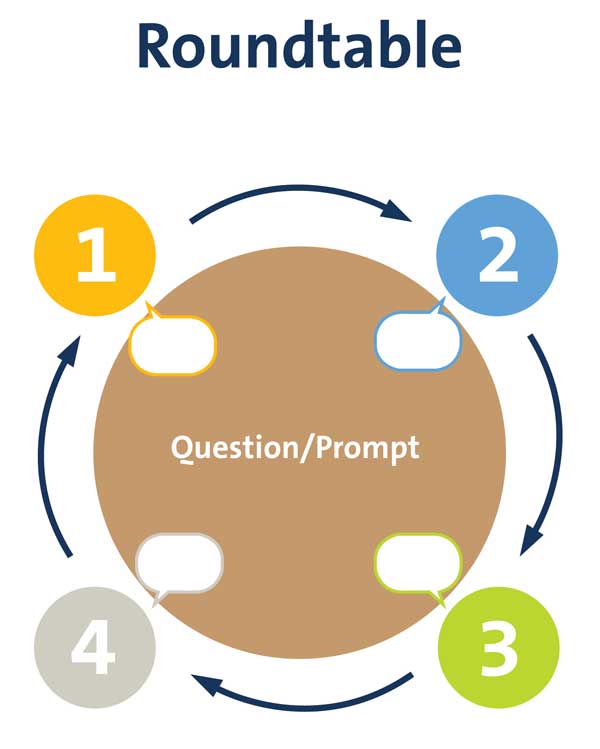

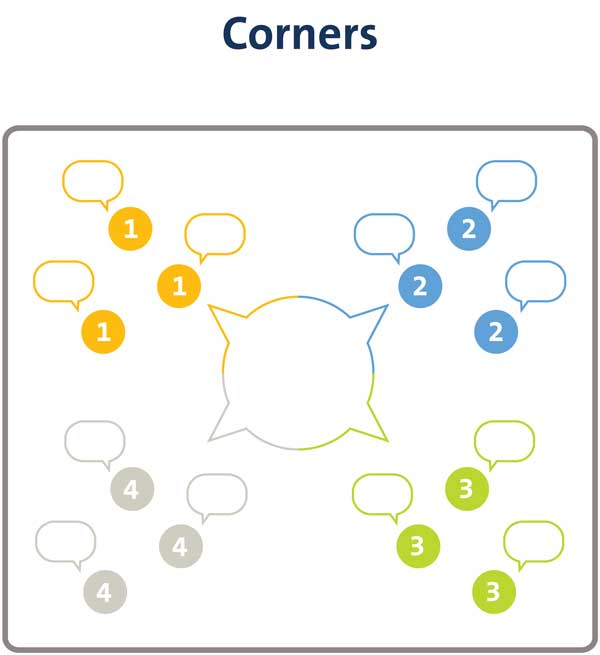

Post a debatable topic, issue, or question. Designate one end of a line as the Yes/Positive response and the other end as the No/Negative response. Have students express the strength of their response by voting with their feet to stand at either end or anywhere along the continuum that reflects their thinking. Where clusters of students collect on the continuum, have them discuss and then share ideas through a spokesperson. Where students are outliers, invite them to share constructively their unusual thinking. At the end of the activity, poll all students collectively or anonymously, to learn if any students changed their minds.CORNERS

Assign each corner of the room a part of a topic. Allow students to think or write independently about the top-level topic. Then have them congregate in the corner of their choice: the part, aspect, view, that interests them. Students in a corner share ideas. Then one student shares the discussion output with the class. This routine allows students to take a position through their movements and then to explore their ideas in discussion with those with common views. Subsequent discussion with the whole class promotes a range of views and even subtle aspects of generally similar views.

Corners and sides is an adaptation allowing for additional locations/continuum between corners.

ESTIMATION LINE-UP

Ask a question that students can answer with a numerical response based on a sliding scale. Place a number line around your classroom walls, adapting the range to students’ age and counting capacity. Have students stand under their number/answer, prepared to share why. Then, “fold the line in half” so the students who most strongly disagreed with each other briefly exchange ideas before sharing with the whole class.

FEEDBACK

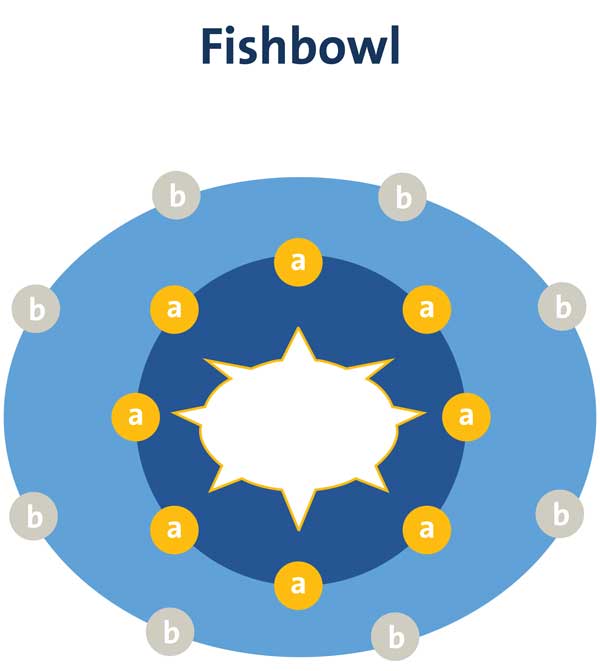

FISHBOWL

Organize students in two large and equal groups. Students in the inner face each other and discuss the assigned topic. Students in the outer circle face inward to observe and listen to the fishbowl discussion. Prompt the outer circle students with a specific purpose for listening, such as to identify new information or evaluate the discussion against provided criteria. When time allows, reverse the roles and positions. This routine is particularly useful for Socratic seminar lessons.

FUN WITH LOGISTICS

Use and adapt these methods to a range of classroom activities and purposes.

- Line up: To organize students for many activity types, have them line up/stand up/step forward, etc. according to criteria, such as age, height, information you have distributed (a name, number, etc.). For example, students might have a card containing the title of a recently read book or story character. They arrange themselves in lines by book title, books from same module, characters who X (e.g. are children, have names starting with a particular letter, face a difficult challenge, etc.).

- Form Groups/Pairs: To create groups, whether same- or mixed-ability, use engaging methods that offer variety and reinforce other learning. Examples: call out 1, 2, 3, 4, with students gathering in same- or mixed-number groups; name a color and group students wearing it or who rank it as a favorite, call out letters and group students whose name or birth month start with that letter. Be mindful of methods that require students to rank themselves in ways that may feel critical, such as by height. See Grouping for more.

- Find the Answer: Provide students with incomplete information, such as the list of characters from a book or one part of a cause-effect relationship. Have students circulate and mingle, interviewing classmates until they find the specified information. Students may survey each other to collect information or be directed to find their match with the missing information.

- Join the Crowd: Provide a starting question or topic. Have students circulate randomly. Signal them at intervals to stop and talk to the nearest student. Signal again after 1–2 minutes for students to circulate again. Signal another sharing, either of the newly received information or the original topic.

- “I’m done!”: When students finish an activity or assigned task quickly, it’s useful to have a range of options ready to engage them. Here are some ideas:

- Library/Newsstand: Prepare with articles or enrichment books related to current classroom study or topics of particular interest to your students. Invite students to read an article, book, or book chapter for extra credit, to share information with peers, to find evidence for writing tasks, to work ahead in reading homework, or for personal enrichment.

- Digital Download: Prepare available classroom computers with activated appropriate software or bookmarked appropriate websites. Invite students to use the software or designated web sites for approved purposes, such as to play educational games, conduct research, interact with pen pal student communities, and so on.

- Suggestion Box: Prepare an area for writing and journaling, on paper or at computers. Invite students to write to share ideas with you, the whole class or school, or the broader literary community. For example, they can list class trips they’d like to take, questions for an author, topics they want added to the school curriculum, and so on. Provide a physical or digital suggestion box or allow students to keep their ideas private.

- Word Games: Provide a collection of word study activities, such as Sudoku, word searches, crosswords, or word puzzles. Invite students to complete activities independently, in pairs, or in groups.

- Take the Challenge: Prepare a station by posting a challenging problem for students to attempt. Clarify that there will be no grading nor are they required to complete the problem. Allow students to work independently or with peers.

GALLERY WALK

Post student work or content you want students to analyze on classroom walls. Have students circulate alone, in pairs, in groups, and so on. Direct students toward the specific desired response, such as to annotate classmates’ work with a Star and a Step or to write a question about the posted content. This routine can be endlessly adapted. Be creative!

GO GO MO (Give One, Get One, Move On)

Distribute three index cards or sticky notes to each student.

- Ask students to identify 3 examples of something (a detail they found, a main idea, the theme of a story, causes or effects, solutions to a problem, and so on). Pre-literate students may think of 3 items, or if that is too many to remember, reduce the number.

- Tell students to write each example on an index card or remember it.

- GO-GO: Have students mingle to exchange one idea with someone else and discuss. (60 seconds)

- MO: Move on to repeat.

GROUP DISCUSSION

Ask questions to the class or groups, and elicit answers from volunteers. This routine is particularly useful for building literal understanding, where any correct answer from any single student supports learning by all students. It is also useful when time is short because it can be more efficiently managed than student-led collaborative discussion.

GROUPING

There are many ways to organize students for learning, each of which has advantages and disadvantages in different situations. You can also modify grouping by criteria, such as ability (mixed- or same-ability groups), size (small or large groups), and so on. Be creative to reflect the needs of your classroom and students.

Individual:

- Benefits: Students can work at their own paces and in their own learning styles. Teachers can observe and assess individual capacities and progress. Creates a relatively quiet and orderly classroom that supports student reflection.

- Disadvantages: Students lose creative energy of collaboration and scaffolding from peer support, leaving them more isolated and perhaps limited by their own collection of strengths and weaknesses.

Pairs:

- Benefits: Students learn from each other and practice interacting socially 1:1, yet become accountable for their learning. Shyer or quieter students participate more comfortably, especially if sharing private information or risking an incorrect answer. This pairing invites students to take learning risks and move toward the edge of their knowledge comfort zone, where most learning occurs. In addition, materials and classroom tools can be shared.

- Disadvantages: Classroom may be noisy if there are a lot of pairs. Students who are inappropriately paired will struggle. It’s difficult to assess individual progress.

Small Groups:

- Benefits: Targeted discussion enables group members to support each other’s learning and hold each other accountable for tasks, comprehension, and content contributions. Mixed-ability groups can balance each other’s strengths and weaknesses, while same-ability groups can work at a shared and appropriate pace to balance challenge and scaffolding. Materials and classroom tools can be shared. It can help you to save time during research, difficult reading, or other informative-intensive work.

- Disadvantages: The classroom may be noisy or disorganized if there are a lot of groups or groups are large. Groups that are assembled or have unbalanced skills and knowledge may struggle. It’s difficult to assess individual progress.

Whole Class:

- Benefits: Teachers can present same content to many students very efficiently. Students can benefit from each other’s knowledge during Q&A or other knowledge-building where solving the problem is more important than who solves it. Whole groups are also useful for activities with many roles to fill, such as debates, or where a class population reflects many skills sets and interests.

- Disadvantages: Whole class work may emphasize teacher-centered learning and limit active, student-centered learning. Whole class collaborative work can be challenging to manage, especially if the class is large.

Mixed-Ability Groups:

- Benefits: Students learn from each and support each other’s learning styles. Students support each other’s pace, improving timeliness for the whole group. Variety in student interest limits competition for roles, for example allowing an artistic student to play a comfortable role while the social student conducts interviews. Students benefit from peer teaching and learning.

- Disadvantages: Students working at different paces may get frustrated with each other, creating pressure on slower learners and boredom for quicker learners, and reducing motivation for both groups. Tension can also result—and cause inefficiency—if students cannot agree or cannot align their efforts. Tension also impedes learning for some students.

Same-Ability Groups:

- Benefits: Students can work at a shared and comfortable pace, and engage in activities suited to shared learning style. These shared goals and learning habits may yield greater harmony, improving the learning environment for some students. Placing students in same-ability groups also means that students have to try new roles—they cannot always have the “artist” role—which creates the opportunity to learn from unfamiliar roles.

- Disadvantages: Lack of diversity—in skills, knowledge, interest level, learning style, etc.— can reduce creativity and diminish learning. Students may compete for roles if they share similar preferences. Similar interests and abilities may lead to increased socializing that distracts from learning. Students may have some shared abilities yet some sharply contrasting other factors, such as learning rate.

HEADS TOGETHER

Organize groups of 4–6 students and provide a question to answer or problem to solve. Students must collaborate, or put their “heads together” to generate a response. Explain that you will cold call one student to answer for the group (this encourages everyone to participate.) This routine is useful for activating students’ background knowledge or debriefing their learning from classroom activities and reading.

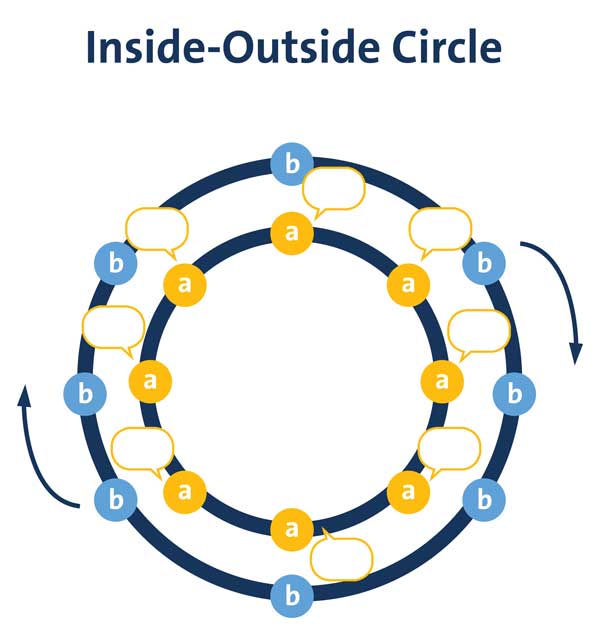

INSIDE-OUTSIDE CIRCLE

Organize two large and equal groups. Groups face each other in concentric circles, each student paired with a partner from the opposite group. Have students in the outer circle ask a question; students in the inner circle answer. Signal students to rotate the circle and create new pairings. You can also signal students to reverse asking and answering roles.

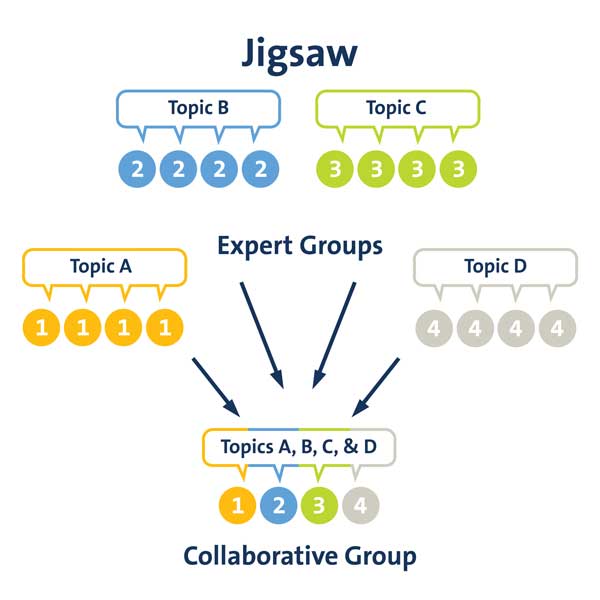

JIGSAW

Organize expert groups and assign topics. Students will become the expert on their topic. Then reorganize new collaborative groups including an “expert” from each original group. In the new collaborative group, students share their expertise with each other. This activity facilitates research, analysis, reading, and so on in an efficient manner, builds student accountability and confidence, and reinforces effective discussion habits.

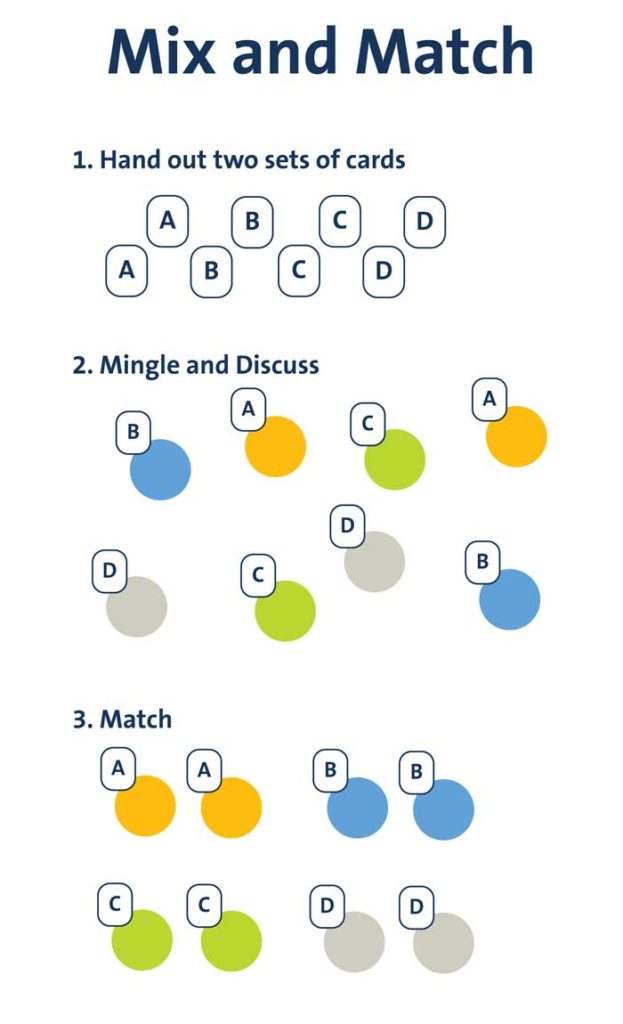

MIX AND MATCH

Prepare matching cards, slips of paper, sentence strips, or other materials that can be matched in pairs, e.g. a question and its answer, a word and its definition. Distribute one card, slip, strip, etc. to each student. Have students circulate to discuss their information. Then signal them to find a match. After each match, have student exchange their card, slip, strip, etc. Repeat as time allows.

POPCORN

Developed by Regent University, this routine can be used for sharing, reading for general understanding (Gist and Joy), or any other discussion-based activity. Use it to encourage participation, recognizing that some students will sit out and piggyback on classmates’ efforts. As such, confine popcorn to situations in which everyone benefits from watching, such as clarifying basic facts in a reading.- Start with a question, challenge, or prompt that has multiple answers/solutions.

- Have students think briefly.

- Call “Popcorn.”

- Volunteers should “pop up” to stand and share an answer. Clarify if students should answer one at a time or as a group.

- Have listeners respond, correct, and record corrected answers. Lead discussion to clarify any remaining confusion.

- Alternatively, students can lead the questioning after step 2, asking each other the initial prompt one at a time.

Q AND A

Provide students with practice in asking and answering questions about specific aspects of a text or task. Example As students read, have them list 1-2 questions they can ask a partner, the class, or a group to identify details that support the inferences they draw. Have listeners answer.READER’S THEATER

Have students perform a portion of a text in play format. This routine works well for texts with rich dialogue and provides an authentic reason for reading aloud and practicing basic comprehension/fluency skills.ROLES FOR COOPERATIVE GROUPS

This routine is applicable to many group projects and routines. Use it to organize collaborative work by defining familiar roles for students and then assigning these roles to reinforce. Some common roles are supervisor, recorder (scribe), information gatherer (research), materials gatherer, illustrator, and so on. You can assign these roles in mixed-ability groups according to students’ areas of strength, in same-ability groups according to students’ learning style preference, or in a range of other ways. Organizing collaboration with clear and familiar roles helps students complete tasks with confidence, holds them accountable for specific responsibilities, and insures that all students participate in group work.

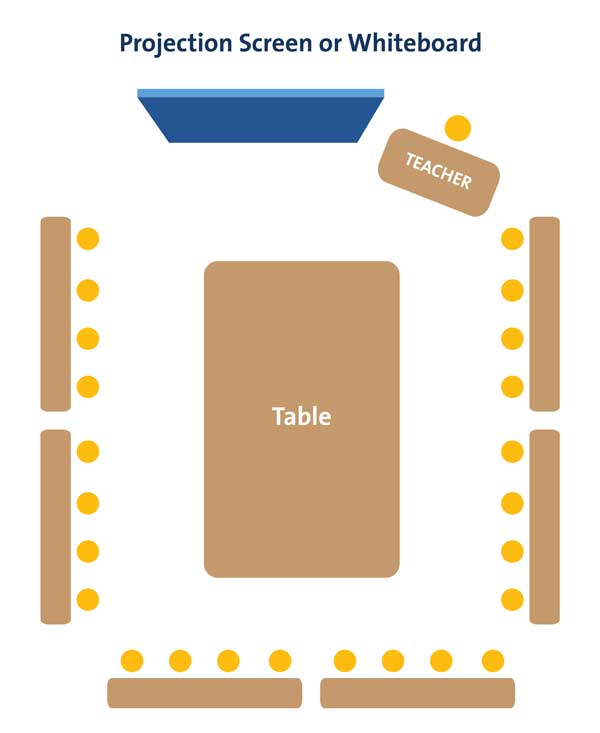

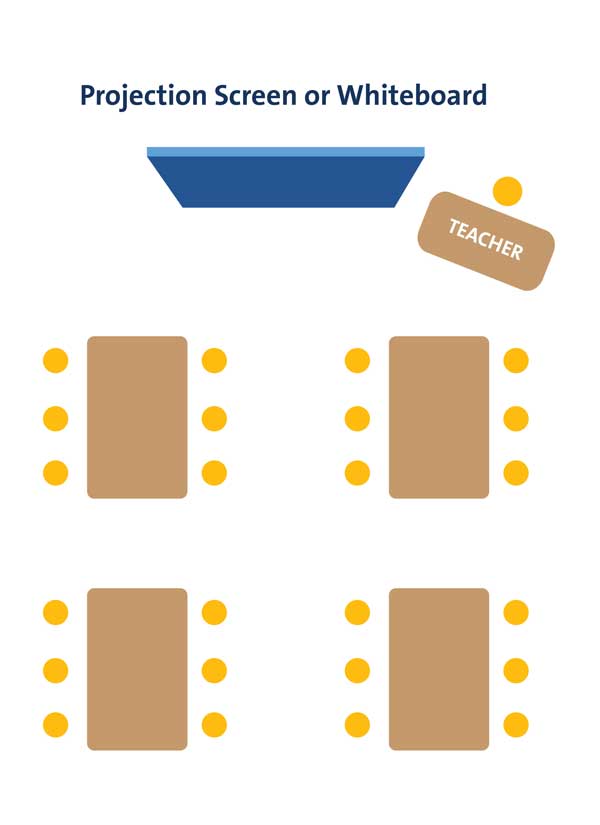

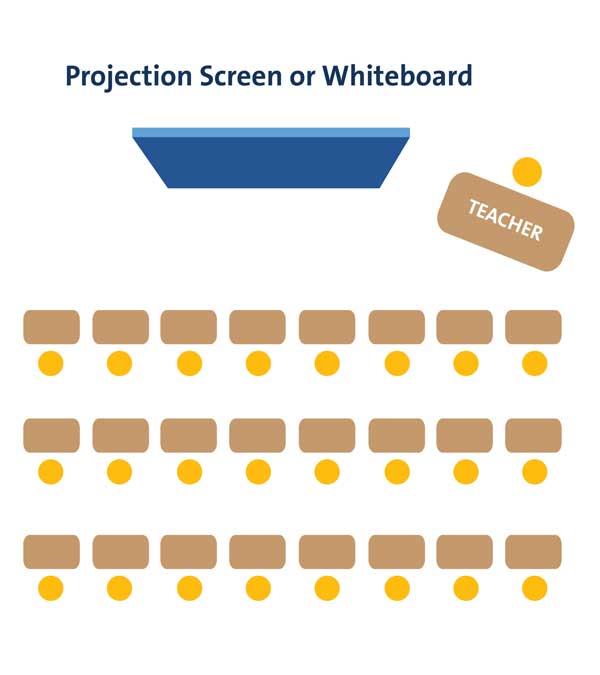

SEATING

There are many ways to organize classroom seating, each of which has advantages and disadvantages. This section shows in graphic form—and explains—some main seating options and briefly describes benefits/appropriate use of each. you can modify most seating arrangements in various ways. Be creative to reflect the needs of your classroom and students.

To build the best seating plan for a given day or activity, consider:

- Student safety and classroom decorum: You and students must be able to circulate safely, see and hear each other, access shared materials, and so on. You must also be able to maintain classroom decorum, even during collaborative work. In general, you should allow enough space around seats or clusters of seats.

- Planned activities: It’s time-consuming to rearrange seating often, so choose a plan that works for most of a day’s activities.

- Desired groupings: If students will work individually, such as for assessment, choose a seating plan that supports privacy and independent work. If students will work collaboratively, choose a plan that supports eye contact, easy discussion at low volume, and materials exchange while seated.

- Required teaching practice: Most seating works best if teachers circulate as there is seldom one place in the room to monitor all student activity. Students also engage more fully when teachers move around.

- Classroom size and number of students: Small groups may be more useful in a large class that is otherwise difficult to manage or limits individual student opportunity. In smaller classes, where everyone can easily see the teacher, you should alter seating plans with instructional goals primarily in mind rather than circulation concerns. Large classes, especially in relatively small classrooms, may offer only limited seating options.

U or V Formation

Organize desks or student tables around a central table, such that all students can see the table and each other. The diagram at the right uses a U formation, which can be varied to a V but omitting the student tables/desks that form the bottom of the U and then arranging the sides using the remaining student tables/desks at an angle to form a V shape.

- Benefits: All students can see each other and the central table. Useful for whole class discussion and shared examination of a presentation or demonstration. Engages students with visual contact and leaves no one overlooked in a back row.

- Disadvantages: Some parts of the classroom will be difficult to access, e.g. walls behind seated students. Hands on access to the materials on the center table is also difficult.

- Circulation Suggestions: Move back and forth between the top and bottom of the U or V or stand at the bottom. These circulation patterns help students focus their attention on the teacher, without blocking their views of each other.

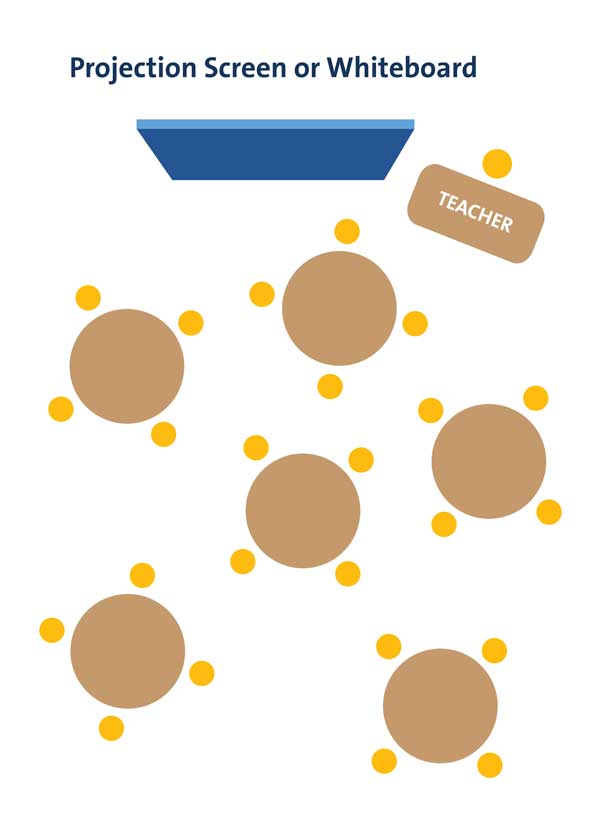

Tables

Organize round or square tables evenly around the room and rectangular tables in evenly spaced rows.

- Benefits: Small groups of students can see each other, exchange ideas, share materials, and collaborate. Useful for both small group discussion/work and whole class discussion/work where the teacher circulates to engage groups or individual students. Engages students more comfortable speaking/contributing in small groups and pulls them away from the forgotten back row.

- Disadvantages: Students may get to chatting in small groups and need reminders to stay on task, especially if the teacher lingers at one table. Close supervision of materials where safety is a concern may also be difficult.

- Circulation Suggestions: Circulate continually among the tables to share information and monitor student behavior. Avoid lingering at any one table.

Rows

Organize desks in horizontal or vertical rows. These rows may be of equal length and width with desks aligned, or you can stagger rows to allow students to see through the rows in front of them.

- Benefits: Students can see the front of the room where whiteboard, presentations, and the teacher are often positioned. Because students’ attention is focused on the front of the room, side conversation is less likely. Useful when presenting shared information to all students or promoting independent work, such as during assessments.

- Disadvantages: Some students are in the back row, where they may be overlooked or disengage from the discussion. Circulation can be difficult, especially if the class is large relative to the room. Students cannot see each other and may sometimes struggle to hear each other. They cannot share materials or easily collaborate. Close supervision of independent work may be challenging if space doesn’t allow circulating through the rows. This formation also encourages teachers to stay at the front of the room, which reduces student engagement

- Circulation Suggestions: If at all possible, circulate to change positions during presentations and lectures. This will keep students engaged.

SLANT

This acronym stands for Sit up, Lean forward, Ask and answer questions, Nod your head, and Track the speaker. It is particularly useful for organized discussions such as Socratic seminars, and it can be applied in any collaborative learning framework, e.g. jigsaw, inside-outside circle, and so on. Teachers should share the acronym with students in age-appropriate ways, such as with characters for each letter and step, or by creating an anchor chart for easy reference.SOCRATIC SEMINAR

A Socratic seminar is a structured discussion that supports students with critical and creative thinking, synthesizing and developing deep comprehension of texts, and refining their thinking in preparation for writing. Socratic seminar features extend student-to-student discussion of ideas, rather than a teacher-driven question and answer format. Socratic seminars can come early in a module, to support inquiry and a purpose for reading, or after reading one or more texts, to support synthesis and create a foundation for writing. Click below to view comprehensive guidance on Socratic seminars.SNOWBALL TO AVALANCHE (also called Avalanche)

Pose a debatable question. Invite students to take a position one at a time, standing to share. Students who agree should stand next to the speaker, forming a “snowball.” Invite a student with a different answer or point of view to stand in another part of the classroom. Students who agree should stand next to the new speaker, thus forming another “snowball.” Allow students to change their minds based on new evidence and ideas presented. Ultimately, though not always, the whole class can come to a consensus, creating an “avalanche.”STUDENT POLL

Invite student engagement by polling students for their views. Collect views in writing, e.g. on sticky notes, index card, or slips of paper, orally by eliciting from volunteers or students in turn, or with gesture such as stand up/sit down.

TALKING STICK

Organize students in circles or any other collaborative seating format and provide a stick or other long object to be the talking stick. The person holding the stick has the turn to speak. Others must listen attentively and respectfully. When finished, the speaker passes the stick to another student. If desired, allow students who don’t wish to speak to pass the stick. This routine works with groups of any size, and for discussions on any topic. However, it is particularly useful when students disagree and have struggled to listen constructively.

TEAM WEBBING

Organize groups of four around a table. Provide a large piece of paper and uniquely colored pens or markers to each student. Assign a topic or task with multiple parts, views, or components, e.g., a word or concept web. Have students respond to the task component on the paper edge facing them. Signal students to turn the paper. Students now repeat the task, this time responding to the new task component now facing them and to the comments already in place from classmates.

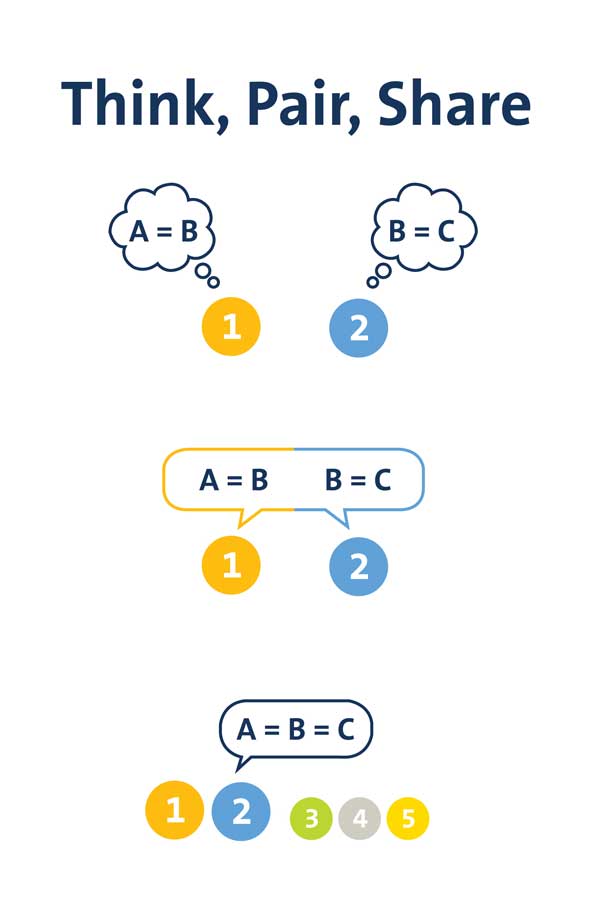

THINK-PAIR SHARE

Organize pairs and assign a topic. Students first think independently about the topic, then they discuss with their partner. Finally, students individually share their ideas with the class. This routine allows students time to develop their own ideas and then exchange feedback on those ideas. It is particularly useful for determining one’s opinion and testing one’s assumptions, but it can be used to brainstorm and collect ideas in many ways.

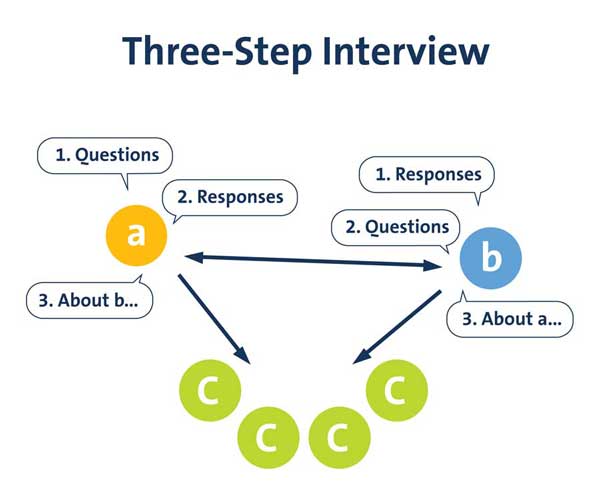

THREE-STEP INTERVIEW

Organize pairs. Direct partners to interview each other about an assigned topic, with each partner asking and later answering questions. Have each student share his/her partner’s information with the class. This routine helps students test their thinking in manageable conversations. It also helps students practice paraphrasing and restating accurately.

TUG OF WAR

This routine can be used to discuss or explore any topic with multiple views. You can use imaginary tug of war rope drawn on the board or add a “vote with your feet” component by having students congregate at either end of an imaginary rope, as in a real tug of war:

- Step 1) Present a fairness dilemma.

- Step 2) Identify the factors that pull at each side of the dilemma. These are the two sides of the tug of war.

- Step 3) Ask students to think of “tugs” or reasons why they support a certain side of the dilemma. Ask them to try to think of reasons on the other side of the dilemma as well.

- Step 4: Generate “what if?” questions to explore the topic further.

For more about Tug of War, see http://www.visiblethinkingpz.org/VisibleThinking_html_files/03_ThinkingRoutines/03e_FairnessRoutines/TugOfWar/TugOfWar_Routine.html

TURN AND TALK

Have students turn to a neighbor and discuss a specific designated question or prompt.

VOTE WITH YOUR FEET

Designate areas of the room for categories of any kind, such as positions on an issue, parts of a research question, opinions, preferences, or any other topic with a range of possible responses. Have students stand in those designated areas to literally vote with their feet.

WALK AND TALK

Organize pairs and allow them to walk around the classroom together as they discuss a provided topic or set of questions.

WHIP-AROUND

Use this routine to collect information and formatively assess students’ knowledge. Share a question or prompt with many answers. Have students list all the possible answers. Then rapidly call on students one at a time to share one response, reminding them not to repeat any already shared. When everyone has shared, challenge students to identify most common ideas and themes.

WORD BANK

Rationale: A word bank or glossary supports students with key words to help comprehend reading, and also provides structure to discussion.

How to Use This Routine:

Provide a bank of important vocabulary words that students will need in their responses. Target words that are important to comprehension that students may not know. This may include Tier 1 for English learners as Tier 2 and 3 words for language learners. Provide a short definition or image for each word. (Find Tier 2 and Tier 3 words easily on Handout: Module # Tier 2 and Tier 3 Vocabulary.)

Example

- WORD BANK:

circulatory system, blood, oxygen, hemoglobin, blood vessels, heart, pump.

Try to use at least 3 of these words in your paragraph.